Your Attic Might Be Hiding a Fortune: The Modern Way to Decode High-Value Pottery Marks

That dusty vase sitting on your grandmother’s mantelpiece might look like a simple vessel for flowers, but to a trained eye, it could be a historical document worth thousands of dollars. For decades, the world of antique pottery has been a playground for those who know how to read the "secret language" written on the bottom of a plate or the curve of a porcelain jar. Most people see a smudge of blue ink or a faint scratch in the clay and dismiss it as a manufacturing defect, yet these marks are the fingerprints of history.

Learning how to identify old pottery marks is the difference between selling a masterpiece for five dollars at a garage sale and realizing you’ve found a museum-quality relic. It requires a blend of tactile intuition, historical knowledge, and, increasingly, the right digital tools. You don't need a PhD in art history to start finding treasures; you just need to know what your eyes should be looking for.

This guide will walk you through the physical characteristics of high-value marks, the legendary brands that collectors hunt for, and the modern methods used to verify authenticity in seconds. By the time you finish reading, you will look at every ceramic object in your home with a completely different perspective.

The Anatomy of a High-Value Maker Mark

Before you start memorizing logos or brand names, you have to understand the physical nature of how marks are applied to clay. A mark isn't just a label; it is a physical part of the object’s manufacturing process. The method used to apply a mark can often tell you more about a piece’s age than the actual design of the logo itself.

Distinguishing Between Incised, Stamped, and Underglaze Marks

The earliest pottery marks were almost always incised. This means the artist or factory worker used a sharp tool to carve initials, numbers, or symbols directly into the wet clay before the piece was fired. When you run your finger over an incised mark, you can feel the depth and the "burr" of the clay. These marks are common in 18th-century European porcelain and 19th-century American stoneware. Because they were done by hand, they are often slightly irregular, which is a hallmark of artisanal, pre-industrial production.

As the Industrial Revolution took hold, factories needed a faster way to brand their goods. This led to the rise of the stamped or "impressed" mark. Unlike incised marks, which are "drawn," impressed marks are made using a metal or wooden die pressed into the clay. These are much more uniform and indicate a higher level of production consistency. If you find a mark that looks perfectly geometric and deep, it likely dates from the mid-19th century onwards.

Then there are underglaze and overglaze marks. An underglaze mark is painted or printed onto the "biscuit" (fired but unglazed clay) and then covered with a clear protective glaze. These marks are permanent and cannot be scratched off. Overglaze marks, however, are applied after the final firing. They often feel slightly raised and can wear away over time. High-end factories like Meissen often used underglaze blue because it was difficult to forge and lasted forever.

The Evolution of Maker Signatures Through the Centuries

The way potters signed their work changed as global trade expanded. In the 1700s, a mark might just be a single hand-painted letter or a simple symbol like an anchor or a crown. These were intended for internal factory tracking or to signify quality to local buyers. There was no legal requirement for complex branding because most pottery didn't travel very far from the kiln where it was born.

This changed dramatically in the late 1800s due to international trade laws. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 required that all decorative items imported into the United States be marked with their country of origin. This is a vital clue for any collector.

- No Country Name: Usually indicates a piece made before 1891.

- "England" or "France": Indicates a piece made between 1891 and roughly 1914.

- "Made in England": Usually points to a production date after 1914.

Pro Tip: If you see a mark that includes a Royal Warrant (like "Potters to the Late Queen Mary"), you can narrow down the production date to the specific years that monarch reigned or shortly thereafter.

| Mark Type | Physical Characteristic | Common Era |

|---|---|---|

| Incised | Carved into wet clay | Pre-1850 |

| Impressed | Pressed with a die | 1850–1920 |

| Transfer Print | Ink printed under glaze | 1880–Present |

| Hand-Painted | Applied with a brush | All Eras (High End) |

Blue-Chip Pottery Brands and Their Signature Stamps

Once you understand how a mark is physically applied, you can start looking for the "blue-chip" names. These are the brands that have maintained their value for centuries and are the primary targets for serious collectors.

European Porcelain Giants and the Meissen Legacy

Meissen is the undisputed king of European porcelain. Founded in 1710 in Germany, it was the first factory to master the secret of hard-paste porcelain, which had previously only been known in China. Their signature mark—the "Crossed Swords"—is perhaps the most famous symbol in the world of ceramics.

However, the Crossed Swords mark has changed dozens of times over 300 years. In the early 1720s, the swords were thin and spindly. By the mid-18th century, they became more curved. During the "Marcolini Period" (1774–1814), a small star was added between the hilts. If you find a piece with a dot between the blades, you’re looking at the "Academic Period." These tiny variations can mean a difference of tens of thousands of dollars in value. Collectors look for the "underglaze blue" swords, which signify the highest quality of Meissen production.

Wedgwood is another titan, but their marking system is entirely different. Unlike the painted marks of Meissen, Wedgwood almost always used impressed marks. The word "WEDGWOOD" in all capital letters is the standard. If you see "Wedgwood & Bentley," you have found a piece from the partnership era (1768–1780), which is highly coveted. Later pieces might include a three-letter code that tells you the exact month and year the piece was made.

American Art Pottery and the Roseville Revolution

In the United States, the "Golden Age" of art pottery occurred between 1880 and 1940. Brands like Roseville, Rookwood, and Paul Revere Pottery created pieces that are now staples of high-end auctions.

Roseville is famous for its floral designs and matte glazes. Early Roseville marks were often just paper labels, which have usually fallen off over time. Later, they moved to "RV" marks and eventually to the "Roseville" script mark that is raised from the bottom of the pot. Because Roseville was so popular, it was heavily faked. Genuine marks should be crisp; if the "Roseville" name looks blurry or "mushy," it might be a modern reproduction.

Rookwood, based in Cincinnati, used one of the most ingenious marking systems in history. Their "RP" logo (the R reversed against the P) was first used in 1886. For every year after that, they added a small flame point around the logo. A mark with 14 flames indicates the year 1900. After 1900, they added Roman numerals below the logo to indicate the year (e.g., "XX" for 1920). This system makes Rookwood one of the easiest brands to date with absolute precision.

Identifying Value When the Stamp is Faded or Missing

What happens when you flip a beautiful bowl over and find... nothing? It is a common misconception that an unmarked piece is a worthless piece. In fact, many early 18th-century masterpieces and experimental 20th-century studio pottery were never marked at all. In these cases, you have to read the clay itself.

Reading Clay Bodies and Glaze Patterns as Fingerprints

The "clay body" is the actual material used to make the piece. If you hold a piece of pottery up to a strong light and you can see the shadow of your fingers through the other side, it is bone china or porcelain. If it is heavy, thick, and opaque, it is likely earthenware or stoneware.

Glazes also act as signatures. Take "Flow Blue" for example. This was a technique where cobalt blue glaze was intentionally allowed to "bleed" into the white background during firing, creating a dreamy, blurred effect. While many factories made Flow Blue, the specific shade of cobalt and the "depth" of the bleed can point to specific English makers like Alcock or Davenport, even without a stamp.

Another famous glaze is "Oxblood" (or Sang de Boeuf). This deep red, mottled glaze is notoriously difficult to achieve. It requires a specific reduction firing process in the kiln. If you find a piece with a true, rich Oxblood glaze that transitions into a pale green or white at the rim, you are likely looking at a high-value piece of Chinese porcelain or a high-end American art pottery piece like Chelsea Keramic.

Identifying Period-Specific Shapes and Foot Rims

The "foot rim"—the ring of unglazed clay on the bottom that the piece stands on—is one of the most honest parts of a ceramic object. It is the one place where the potter’s process is laid bare.

- Hand-Turned Rims: On older pieces, you will often see "chatter marks" or slight irregularities where the potter used a tool to trim the excess clay while the piece spun on a wheel.

- Stilt Marks: Look for three small, rough spots on the bottom of a plate. These are marks left by the "stilts" used to prop the plate up in the kiln so it wouldn't stick to the shelf. While modern pottery is fired differently, these marks are a classic sign of 18th and 19th-century production.

- Orange Peel Texture: Some glazes, particularly on 18th-century salt-glazed stoneware, have a pitted texture that looks exactly like the skin of an orange. This is a result of salt being thrown into the kiln at high temperatures and is a key indicator of age.

The shape of the piece, or the "form," also tells a story. A teapot with a low, heavy "squat" body and a straight spout is typical of the early Georgian period. A tall, slender vase with "whiplash" curves and asymmetrical handles screams Art Nouveau. These stylistic clues can help you narrow down a maker even when the mark has been worn away by centuries of cleaning.

Digital Shortcuts for the Modern Collector

For a long time, the only way to identify a mystery mark was to sit down with a massive, 800-page encyclopedia of pottery marks and flip through thousands of tiny black-and-white illustrations. It was a tedious process of "does this crown look like that crown?" Often, beginners would misidentify a mark because they missed a tiny detail, like the number of points on a star or the direction a lion was facing.

Why Manual Lookup Tables Often Fail Beginners

Manual research is a fantastic skill, but it has a steep learning curve. Many marks look nearly identical to the untrained eye. For example, there are hundreds of different "crown" marks used by European factories. If you don't know the difference between a five-pointed coronet and a closed imperial crown, you might mistake a common 1920s souvenir for a 1780s royal gift.

Furthermore, books can't help you with the "feel" of a piece. They can show you what a mark looks like, but they can't tell you if the glaze on your specific vase matches the mark on the bottom. This is where the gap between a hobbyist and a professional appraiser becomes apparent.

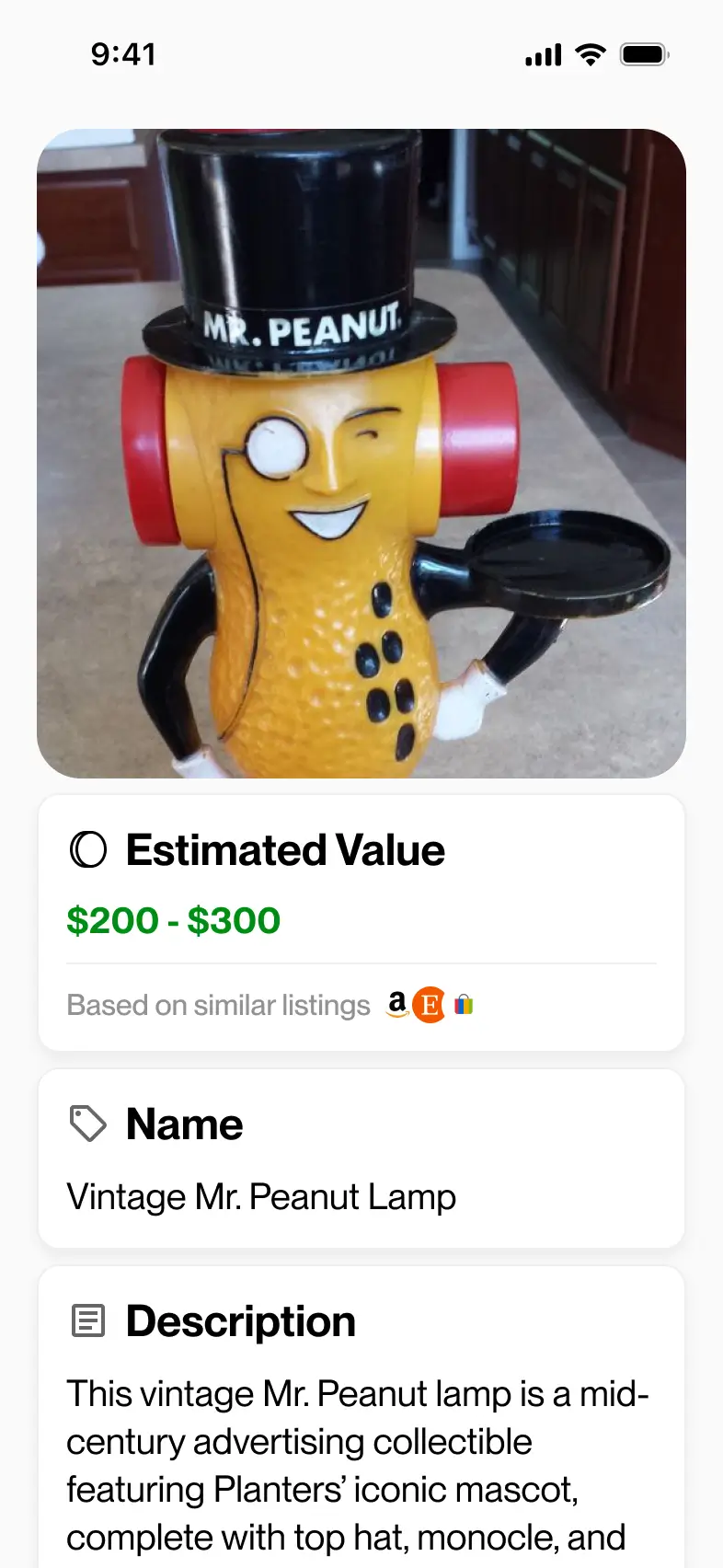

Using Relic to Bridge the Gap Between Photo and Appraisal

This is where modern technology has changed the game for collectors. Instead of spending hours squinting at reference books, you can now use your smartphone to get an instant answer. The Relic app is a specialized antique identifier designed to handle the complexities of pottery and porcelain.

The workflow is simple: you take a clear photo of the mark and the overall piece. Relic’s advanced AI doesn't just look at the logo; it analyzes the glaze, the form, and the texture of the clay. It then cross-references this data with a massive database of verified antiques to provide a real appraisal, history, and origin of the item.

For someone asking, "What is the app that identifies pottery marks?" Relic is the professional-grade answer. It removes the guesswork that leads to "forgery fatigue." Whether you are at a dusty estate sale or cleaning out an attic, having an AI-powered appraiser in your pocket allows you to make informed decisions in seconds. It bridges the gap between seeing a "pretty blue jar" and knowing you’re holding a 19th-century piece of Meissen.

Avoiding the Forgery Trap in the Secondary Market

As long as pottery has been valuable, people have been trying to fake it. Some forgeries are so good they have sat in museums for decades before being discovered. To protect yourself, you have to look past the mark and look at the "honesty" of the piece.

Red Flags of Modern Reproductions and Fake Marks

One of the most common tricks forgers use is the "cold stamp." This is a mark applied to a piece after it has already been fired and glazed. Because it wasn't fired with the piece, a cold stamp can often be scratched off with a fingernail or dissolved with a bit of acetone. Genuine high-value marks are almost always fused into the glaze or the clay body.

Forgers also try to "age" new pottery to make it look like a 200-year-old find. They might soak a new vase in strong tea or coffee to stain the unglazed foot rim, giving it a brown, "dirty" look. They might even use acid to dull the shine of a modern glaze.

- Uniform Wear: Look at the bottom of the piece. On a genuine antique, the wear should be uneven. It should be heaviest on the parts of the base that actually touch the table. If the entire bottom is perfectly and evenly scratched, someone likely used sandpaper to fake the age.

- The "Samson" Factor: The Edmé Samson factory in Paris was famous in the 19th century for making high-quality copies of Meissen, Chelsea, and Chinese Export porcelain. While they originally marked their pieces with their own "S" mark, these marks were often ground off by later unscrupulous dealers to sell the pieces as originals. Today, "Samson" pieces are collectible in their own right, but they are not worth nearly as much as the 18th-century originals they mimic.

The Role of Provenance and Patina in Valuation

Patina is the "soul" of an antique. In pottery, this manifests as fine "crazing" (tiny cracks in the glaze) that has darkened over time, or slight mineral deposits inside a vase from years of holding water. These signs of use are actually a collector's best friend because they are incredibly difficult to replicate convincingly.

Provenance—the documented history of who owned the piece—is the ultimate gold standard for valuation. If a piece comes with an original receipt from a famous gallery or was part of a known estate, its value can double or triple. However, most of us don't have a paper trail. In that case, the physical evidence of the mark, the quality of the glaze, and the verification from a tool like the Relic app become your primary safeguards.

Key Insight: A mark is a claim, but the clay is the proof. If a mark says "1750" but the clay is a bright, bleached white only possible with 20th-century chemicals, trust the clay.

Conclusion

The world of high-value pottery is a mix of art, chemistry, and detective work. By understanding the difference between an incised mark and a stamped one, and by recognizing the signature styles of giants like Meissen or Rookwood, you turn every thrift store visit into a potential treasure hunt. You no longer have to wonder "how to identify old pottery marks" with uncertainty; you now have the framework to categorize and evaluate almost any ceramic piece you encounter.

Remember that while your eyes and hands are your first line of defense, technology is your greatest ally. Using the Relic app allows you to verify your intuitions with professional-grade AI, ensuring that you never walk away from a fortune or overpay for a clever fake.

Next time you see a piece of pottery that catches your eye, don't just look at the decoration. Flip it over. Run your fingers across the base. Look for the "chatter" of the potter’s wheel and the "bleed" of the cobalt. Your attic—or the shelf of a local charity shop—might just be hiding the next great historical find. All you have to do is start looking.

Identify antiques instantly

Point your camera at any antique, collectible, or vintage item. Get valuations, history, and market insights in seconds.

Download for iPhone