Your Grandmother’s Dresser Might Be a Masterpiece—Here’s How to Prove It

That heavy, dark dresser sitting in your guest room might seem like nothing more than a sturdy place to store extra linens. It has been in the family for generations, moved from house to house, and perhaps even relegated to the garage at some point. But before you consider sending it to a thrift store or painting it a trendy shade of teal, you owe it to yourself to look closer.

Furniture from the pre-industrial era wasn't just built; it was engineered by hand with a level of precision that modern machinery struggles to replicate. These pieces carry the "fingerprints" of their makers—subtle clues hidden in the joints, the underside of the drawers, and the very texture of the wood. Identifying these marks is the difference between owning a mass-produced replica and a valuable piece of history.

By the time you finish reading this, you will know how to read the language of old wood and iron. You will understand why a "mistake" in a dovetail joint is actually a mark of high value, and why the rough texture on the back of a cabinet is more important than the polished finish on the front. Let’s turn you into a furniture detective.

Evidence of the Human Hand

When you look at a modern piece of furniture from a big-box store, every edge is perfectly straight and every joint is identical. This uniformity is the hallmark of a machine. To find a true antique, you have to look for the opposite: the beautiful, subtle irregularities of the human hand. Before the mid-19th century, every board was planed by hand, and every joint was cut with a manual saw.

Joinery and Construction Marks

The most famous "tell" in antique furniture is the dovetail joint. This is the interlocking series of "teeth" that holds drawer fronts to their sides. In a modern factory, a high-speed router cuts these joints with mathematical precision. They are perfectly spaced, perfectly shaped, and usually quite numerous.

A pre-1850s craftsman, however, had to cut each of these by hand using a fine-toothed saw and a chisel. Because this was labor-intensive, they used as few as possible. A genuine 18th-century drawer might only have two or three large, slightly irregular dovetails. If you look closely, you might even see "over-cut" marks—tiny nicks where the craftsman’s saw went just a fraction of an inch past the line. These aren't defects; they are proof of origin.

The Detective’s Rule: If the joinery looks too perfect to be true, it probably is. Look for the "pins" (the thin parts of the dovetail) to be narrow and the "tails" to be wider. This "skinny pin" look is a classic sign of high-end hand craftsmanship.

Beyond the dovetails, look at the back and underside of the piece. Before the invention of the circular saw in the mid-1800s, logs were processed using a pit saw—a massive two-person saw that moved up and down. This left straight, somewhat irregular vertical or diagonal marks on the wood. If you see circular, curved saw marks, the wood was cut after 1850. If the wood is perfectly smooth and featureless, it was likely processed by a modern industrial planer.

Symmetry and Natural Imperfections

Human beings are remarkably good at making things look symmetrical, but we are not machines. If you measure two "identical" legs on an 18th-century chair with a caliper, you will find they are off by a few millimeters. This is because the craftsman worked by eye and feel.

Run your hand across the top of a large surface, like a tabletop or the side of a dresser. Does it feel perfectly flat like a sheet of glass? Or do you feel slight, rhythmic undulations? These "planing marks" occur when a craftsman uses a hand plane to smooth a board. Even the most skilled worker leaves behind these long, shallow valleys that you can feel better than you can see.

- Hand-Cut Dovetails: Look for few, large, and slightly irregular joints with visible scribe lines.

- Pit Saw Marks: Look for straight, vertical, or slightly diagonal rough lines on unfinished surfaces.

- Hand-Planed Surfaces: Feel for long, shallow waves across wide boards rather than a dead-flat surface.

- Asymmetry: Check for slight variations in hand-carved motifs or turned legs that suggest they were made individually.

Materials That Tell a Story

Once you have examined how a piece was put together, you need to look at what it was made of. The materials used in furniture construction have changed drastically over the last 300 years. A master cabinetmaker in 1780 wouldn't dream of using expensive mahogany for the parts of a dresser that no one would see. Instead, they used a "secondary wood."

Wood Species and Secondary Woods

In the world of antiques, the wood you see on the outside is the "primary wood." This is usually a high-quality hardwood like cherry, walnut, or mahogany. However, the "secondary wood"—used for drawer bottoms, back panels, and internal framing—is where the real secrets lie.

If you pull out a drawer and the bottom is made of thick, solid planks of white pine, poplar, or cedar, you are likely looking at a genuine antique. These woods were cheap and plentiful, making them ideal for structural parts. If the drawer bottom is made of plywood, particleboard, or a very thin veneer, the piece is almost certainly a modern reproduction.

| Era | Common Primary Woods | Common Secondary Woods |

|---|---|---|

| 1700-1750 | Walnut, Oak, Maple | White Pine, Oak |

| 1750-1820 | Mahogany, Cherry | Poplar, White Pine |

| 1820-1880 | Rosewood, Walnut, Oak | Pine, Cedar |

| 1900-Present | Oak, Pine, Plywood | Plywood, Particleboard |

The thickness of the wood also matters. Old drawer bottoms are often surprisingly thick—sometimes up to half an inch—and they are usually "chamfered" or thinned at the edges so they can fit into the grooves of the drawer sides. This level of effort in a hidden area is a hallmark of pre-industrial quality.

Hardware Patina and Fasteners

Hardware is the "jewelry" of furniture, and it provides some of the most reliable dating evidence. Before the mid-19th century, screws and nails were expensive and made by hand.

If you find a screw in your dresser, look at the head. Is the slot perfectly centered? Is the tip pointed? Early screws (pre-1850) were made by hand-cutting threads onto a blank shank. They often have off-center slots, blunt ends, and threads that look slightly uneven. If the screw looks like something you’d buy at a modern hardware store, it’s either a replacement or the piece is newer than it looks.

Nails follow a similar evolution:

- Hand-Forged Nails: These have a square shank and a "rose head" that looks like a flattened pyramid. They were common until about 1800.

- Machine-Cut Nails: These have a rectangular shank and a flat head. They became the standard in the 1800s.

- Wire Nails: These are the round nails we use today, which didn't become common in furniture until the very late 1800s.

Finally, look at the brass handles or "brasses." Genuine old brass develops a deep, mellow patina over centuries. It shouldn't look like a shiny new penny. Look for "oxidation" in the crevices—a dark, almost black buildup that occurs naturally. Whatever you do, never polish this off. In the antique world, original patina is worth more than a shiny surface.

The Evolution of Furniture Eras

If you are wondering "How to tell what era furniture is from?", you have to look at the silhouette. Furniture styles don't change overnight, but they do follow a predictable chronological roadmap. Each era was a reaction to the one before it.

Decoding Period Specific Silhouettes

In the 18th century, the Queen Anne and Chippendale styles reigned supreme. These pieces are defined by grace and curves. You will often see the "cabriole leg," which mimics the curve of an animal’s leg, ending in a "ball-and-claw" foot. These pieces feel light and elegant, even if they are made of heavy mahogany.

By the mid-19th century, the Victorian era brought a love for the dramatic. These pieces are often massive, dark, and covered in intricate carvings of fruits, flowers, and scrolls. If your dresser looks like it belongs in a haunted mansion or a cathedral, it likely dates to the late 1800s.

The 20th century saw a hard pivot toward simplicity. Mid-Century Modern (MCM) furniture, produced roughly between 1945 and 1970, stripped away all the "fussy" carvings. Instead, it focused on the natural beauty of the wood (often teak or walnut) and tapered, "peg" legs.

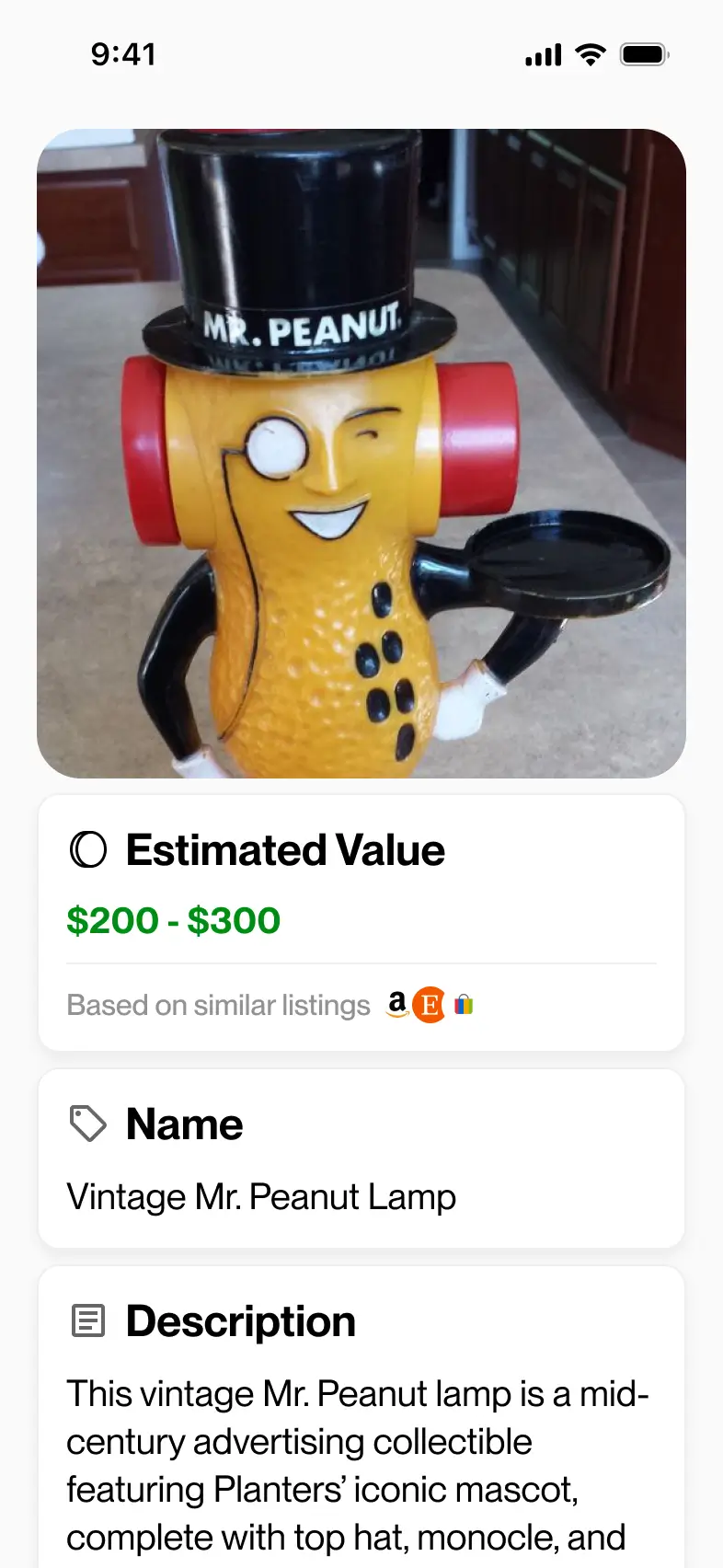

Identifying these styles can be overwhelming because there is so much overlap. This is where modern technology can act as a bridge. The Relic app uses AI to analyze these visual silhouettes instantly. By simply taking a photo, the app can cross-reference the curve of a leg or the shape of a pediment against a massive database of historical designs. It’s like having an art historian in your pocket who can tell you if that curve is "Queen Anne" or "Chippendale" in seconds.

Surface Finishes and Wear Patterns

The way a piece of furniture "glows" can tell you its age. Before the 1920s, most furniture was finished with shellac or wax. Shellac is a natural resin that ages into a deep, rich amber. It is also delicate; it will dissolve if you drop a bit of high-proof alcohol (like a cocktail) on it.

Modern furniture is usually finished with polyurethane or lacquer. These create a hard, plastic-like shell that sits on top of the wood. While durable, they lack the depth and "soul" of an old shellac finish.

The Wear Test: Look at where people would naturally touch the piece. On a dresser, the wood around the handles should be slightly darker or smoother from 100 years of oils from human hands. On a chair, the front rung should show wear from generations of feet resting on it. If a piece is "old" but the wear is perfectly even everywhere, it might be a "distressed" modern reproduction.

Modern Tools for Instant Identification

For a long time, identifying an antique required a library of heavy reference books and years of study. You had to memorize the difference between a "Hepplewhite" shield back and a "Sheraton" square back. If you found a mysterious mark inside a drawer, you might spend weeks trying to track down the maker in an auction catalog.

Using AI to Decode Furniture Origins

The "old way" of identification is being replaced by a much faster, more accurate "new way." Technology has finally caught up with the complexity of antique furniture. The Relic app represents this shift, using advanced AI to do the heavy lifting for you.

When you upload a photo to Relic, the AI doesn't just look at the overall shape. It analyzes the grain patterns, the specific type of joinery visible in the photos, and the subtle "hand" of the carving. It can detect the difference between a hand-carved acanthus leaf and one made by a machine-controlled router.

This is particularly helpful for identifying "transitional" pieces—furniture made during the years when one style was fading and another was beginning. These pieces often confuse human collectors, but an AI trained on millions of data points can spot the specific regional characteristics that reveal a piece's true origin.

Instant Appraisals versus Traditional Auctions

In the past, if you wanted to know what your grandmother’s dresser was worth, you had to contact an auction house or a professional appraiser. This often involved paying a fee and waiting weeks for a response. For many people, the hassle wasn't worth it, so valuable pieces were sold for pennies at yard sales.

Digital tools have democratized this process. With Relic, you get an instant appraisal based on current market data. The app looks at what similar pieces have sold for at auction houses and galleries recently, providing a real-world valuation.

- Speed: Get an answer in seconds rather than weeks.

- Accuracy: AI removes the "guesswork" and human bias from identification.

- Accessibility: You don't need a PhD or a massive library to find a treasure.

- Documentation: You can keep a digital catalog of your items, complete with their history and value, which is vital for insurance purposes.

Protecting Your Investment and Market Value

Once you have identified that your dresser is indeed a masterpiece, your priority shifts to preservation. The antique market is fickle, and what was valuable twenty years ago might not be today. However, the one thing that never changes is that "originality" is the primary driver of value.

Modern Demand for Different Eras

Currently, we are seeing a fascinating split in the market. "Brown furniture"—the heavy, dark mahogany and oak pieces from the 18th and 19th centuries—is currently at a historic low in price. This makes it a "buyer's market." If you have a high-quality Federal-style sideboard, it might not be worth as much today as it was in 1995, but its intrinsic value remains high.

On the other hand, Mid-Century Modern furniture is soaring. A teak dresser from a Danish designer like Hans Wegner can fetch thousands of dollars at auction. The "clean" look fits perfectly with modern interior design trends.

| Style | Current Market Trend | Investment Potential |

|---|---|---|

| 18th Century (Chippendale/Queen Anne) | Stable/Low | High (Long-term) |

| Victorian (Ornate/Dark) | Low | Moderate |

| Mid-Century Modern (Teak/Minimalist) | Very High | High (Short-term) |

| Art Deco (Geometric/Exotic Woods) | High | High |

Preservation Mistakes That Kill Value

The most dangerous thing you can do to a valuable antique is "restore" it without professional guidance. There is a common misconception that an antique should look brand new. In reality, stripping the original finish off an 18th-century piece can reduce its market value by as much as 90%.

Collectors want "crackle," "crazing," and "patina." They want to see the history of the piece. If you strip a 200-year-old finish and replace it with modern polyurethane, you have essentially turned a historical artifact into a used piece of furniture.

Before you touch a piece with sandpaper or chemicals, use the appraisal feature in the Relic app. If the app indicates the piece has significant historical value, your only job is to keep it clean and out of direct sunlight. Professional restoration should only be done by experts who use period-correct materials like hide glue and hand-rubbed shellac.

The Golden Rule of Antiques: It is only original once. You can always restore a piece later, but you can never "un-restore" it.

Conclusion

Your grandmother’s dresser is more than just a piece of furniture; it is a physical link to the past. By looking for the "mistakes" of the human hand, identifying the secondary woods hidden in the frame, and understanding the silhouettes of different eras, you can begin to uncover its true story.

You don't have to be an expert to find a masterpiece. Whether you are crawling through an attic or browsing a local estate sale, the clues are there if you know where to look. And when the physical clues become too complex, digital tools like Relic are there to provide the final piece of the puzzle.

Your Next Steps:

- The Drawer Test: Pull out a drawer and look at the dovetails. Are they few and irregular?

- The Feel Test: Run your hand across the underside of the tabletop. Do you feel the waves of a hand plane?

- The Hardware Check: Look at the screws. Are the slots off-center?

- The Digital Scan: Use the Relic app to take a photo and see what the AI reveals about its history and value.

The next time you look at that old dresser, don't just see a place for socks. See the craftsman who labored over it 200 years ago, and the history that is now sitting in your home. It might just be the most valuable thing you own.

Identify antiques instantly

Point your camera at any antique, collectible, or vintage item. Get valuations, history, and market insights in seconds.

Download for iPhone