Your Thrift Store Find Could Be a Meiji Treasure—Here’s How to Decode Japanese Pottery Marks

You are standing in a crowded thrift store, shoulder-to-shoulder with bargain hunters, when a flash of cobalt blue catches your eye. You pull a small, dusty porcelain vase from the back of a shelf. It feels heavy for its size, the glaze is smooth as glass, and when you flip it over, you see a series of intricate blue characters painted on the base. Is this a mass-produced souvenir from the 1970s, or have you just stumbled upon a piece of Meiji-era history worth thousands of dollars?

The difference between a "find of a lifetime" and a "nice decorative piece" often comes down to a few millimeters of ink or impressed clay. Japanese pottery marks are a complex language of their own, representing centuries of tradition, family lineages, and shifting international trade laws. For the uninitiated, these marks look like an impenetrable thicket of lines and boxes. However, once you learn to decode the visual shorthand used by Japanese potters, the history of the object begins to reveal itself.

This guide will walk you through the essential steps of identifying Japanese ceramics. You will learn how to distinguish between hand-painted signatures and stamped seals, how to spot the subtle physical clues that separate Japanese work from Chinese imports, and how to use modern tools to verify your discoveries in the field. By the time you finish reading, you will look at the bottom of a plate with the eyes of a seasoned collector.

Visual Language of Japanese Ceramics

To understand Japanese pottery marks, you must first understand that you aren't just looking at a name; you are looking at a method of production. Japanese marks generally fall into two categories: hand-painted Kanji and impressed or stamped seal marks. Each tells a different story about when and why the piece was made.

Kanji versus Seal Marks

Hand-painted marks are typically executed in cobalt blue underglaze or iron-red overglaze. These are written in Kanji, the logographic characters adopted from Chinese writing. When you see a hand-painted mark, you are often looking at the work of an individual artist or a small, high-end studio. The brushwork should appear fluid and confident. In older or more artisanal pieces, the "spirit" of the potter is said to reside in the signature. If the lines are shaky or the ink is unevenly pooled, it may indicate a later copy or a less-skilled apprentice.

Seal marks, known as tensho, are different. These are often square or rectangular and look like they were pressed into the clay with a stamp. While some high-quality antique pieces use seal marks, they became incredibly common during the late 19th century and into the 20th century for export wares. A stamped mark suggests a level of standardized production. It was a way for a kiln to "brand" a large volume of work quickly. If you find a mark that looks perfectly geometric and uniform, it is likely a seal mark intended for the international market.

Common Helper Characters

You don't need to be fluent in Japanese to identify the most important parts of a mark. Many marks include "helper" characters that provide immediate context. These characters act like a compass, pointing you toward the era and the intent of the piece.

- Dai Nippon (大日本): This translates to "Great Japan." If you see these two characters, you are almost certainly looking at a piece made during the Meiji period (1868–1912). This was a time of intense national pride and a massive push to export Japanese art to the West.

- Tsukuru or Zo (造): This character means "made by" or "constructed." It usually follows the name of the potter or the kiln. For example, if you see "Kutani Zo," it simply means "Made in Kutani."

- Sei (製): Similar to Zo, this means "manufactured" or "made." It is often found on porcelain from the Arita or Seto regions.

- Kin (謹): This means "respectfully." It is a prefix used by potters to show humility, often appearing as "Respectfully made by..."

| Character | Meaning | Context |

|---|---|---|

| 大日本 | Great Japan | Meiji Era Export (1868-1912) |

| 造 | Made by / Constructed | Follows a name or kiln |

| 製 | Manufactured | Common on Arita/Seto wares |

| 窯 | Kiln | Indicates the specific workshop |

Understanding these characters allows you to narrow down the "who" and "where" before you even begin to identify the specific artist. It’s the difference between reading a whole book and scanning the table of contents.

The Fuku Mark and Symbolic Signatures

One of the most frequent questions new collectors ask is, "What is this square mark that looks like a window?" This is almost certainly the Fuku mark. Unlike a signature that identifies a person, the Fuku mark is a symbolic gesture.

Good Fortune in Kutani and Arita

The word Fuku (福) translates to "happiness" or "good fortune." It is perhaps the most ubiquitous mark in Japanese ceramics, particularly on pieces intended for export during the 19th century. However, the way the Fuku mark is rendered can tell you a lot about the piece's origin.

In Kutani ware, the Fuku mark is often found inside a square frame, painted in a bold, sometimes slightly messy green or black enamel. Kutani potters used it as a general mark of quality and a blessing for the owner. In Arita or Nabeshima porcelain, the Fuku mark might be more refined, sometimes appearing in underglaze blue.

The Fuku mark is not a signature of an artist named "Fuku." It is a brand of auspiciousness, used by various kilns to signal that the piece was made with the intent of bringing luck to its household.

Because so many different kilns used this mark, you cannot rely on it alone to determine value. You must look at the quality of the porcelain itself. Is the painting detailed? Is the gold leaf still intact? A Fuku mark on a mediocre piece of pottery doesn't make it a treasure, but a Fuku mark on a finely potted, eggshell-thin porcelain bowl could indicate a high-end 19th-century export.

Interpreting Abstract Kiln Marks

Beyond Kanji and the Fuku mark, you will often encounter abstract symbols. These are "shop marks" or "kiln marks." Think of them like a modern corporate logo. Instead of a name, a kiln might use a stylized leaf, a cherry blossom, or a series of interlocking circles.

These symbols were used to identify which workshop within a larger pottery village produced the item. This was especially important for tax purposes and quality control. If a batch of plates came out of the communal kiln cracked, the village elders could look at the symbol on the bottom to know which potter was responsible. For you, the collector, these symbols are a puzzle. They often require a specialized database to decode, as many were only used for a few years by obscure family workshops.

Distinguishing Japanese Marks from Chinese Counterparts

One of the biggest hurdles for any collector is answering the question: "Is this Japanese or Chinese?" Because Japan adopted many artistic styles and the writing system from China, the two can look remarkably similar at first glance. However, the physical construction of the piece—the "DNA" of the clay—usually gives it away.

Footrim Construction and Glaze Gaps

The "foot" of a piece of pottery is the circular rim on the bottom that it stands on. This is where the potter’s secrets are hidden. Japanese and Chinese potters had very different ways of finishing this area.

- Japanese Footrims: Japanese potters often left the footrim unglazed. The clay used in Japanese stoneware and porcelain is frequently grittier or more "toothy" than Chinese clay. You might notice that the glaze stops a few millimeters before the bottom of the foot, leaving a clean, exposed ring of clay.

- Chinese Footrims: Chinese porcelain, especially from the Ming and Qing dynasties, often has a very smooth, finely ground footrim. The clay is typically pure white and feels almost like polished stone. The glaze often runs closer to the edge of the foot than on Japanese pieces.

Spur Marks and Kiln Evidence

If you flip a plate over and see three or five small, rough dots that look like tiny grains of sand or chips in the glaze, don't assume the piece is damaged. These are spur marks.

During the firing process, Japanese potters (particularly in the Arita and Imari regions) used small ceramic stilts or "spurs" to support the piece in the kiln. This prevented the glaze from fusing the plate to the kiln shelf. While some Chinese wares use spurs, they are a hallmark of Japanese porcelain production.

- Spur Marks: Small, circular "scars" on the base. Usually arranged in a triangular or circular pattern.

- Sand Grit: Sometimes Japanese "folk" pottery (Mingei) will have actual bits of sand stuck to the bottom, a result of being fired in traditional climbing kilns (Anagama).

Another key difference lies in the Reign Marks. Chinese marks often reference an Emperor (e.g., "Made in the reign of Kangxi"). Japanese marks, while they occasionally reference an era like Meiji, are much more likely to honor a specific potter, a kiln name, or a geographic region. Japanese culture places a high premium on the individual lineage of the craftsman, whereas Chinese marks were often a way of paying tribute to the imperial authority of the past.

Instant Identification Through Advanced AI

The manual process of identifying a mark involves flipping through massive, multi-volume encyclopedias of marks or scrolling through endless forum threads. It is time-consuming, and if you are at an estate sale with ten other people hovering over the same table, you don't have time for a library session. This is where technology has finally caught up with the world of antiquities.

The Relic app is a specialized tool designed to bridge the gap between a mysterious mark and a professional appraisal. Instead of trying to sketch a Kanji character into a search engine, you simply take a photo of the base of your pottery. Relic’s AI, which has been trained on thousands of authenticated antique marks, analyzes the brushstrokes, the clay texture, and the specific "helper" characters to provide an instant history.

- Bridging the Language Barrier: Relic can translate archaic Japanese scripts that even modern Japanese speakers might struggle to read. It recognizes the difference between a hand-painted signature and a stamped export mark.

- Real-Time Appraisals: Beyond just identifying the mark, the app provides context on the item's origin and current market value. If you find a piece of "Satsuma" ware, Relic can tell you if it’s "Royal Satsuma" (a 20th-century mass-produced style) or a genuine 19th-century piece from the Shimazu family kilns.

- Origin Mapping: The app helps you understand where the piece fits in the timeline of Japanese history, from the Edo period to the mid-century modern era.

With over 20,000 reviews and a 4.9-star rating, Relic has become an essential part of the toolkit for professional dealers and "pickers." It allows you to make an informed decision at the point of purchase, turning a gamble into a calculated investment. Whether you are trying to find a pottery marks database online or need a specific identification, having this level of AI-driven insight in your pocket changes the way you shop for antiques.

Valuation and the Authenticity Test

A mark is a claim, not a fact. Just because a bowl says it was made by a master potter in 1820 doesn't mean it was. In the world of Japanese ceramics, "tribute marks" are common. These are marks added to later pieces to honor a famous style or potter from the past. To determine if a mark is genuine, you must look for "honest wear."

Wear Patterns and Age Verification

Turn the piece over and look at the footrim again. If a piece is truly 100 years old, the exposed clay on the foot should show signs of age. It shouldn't be bright white and pristine. Look for:

- Micro-scratches: Tiny scratches on the base where the piece has been slid across tables for decades.

- Patina: The unglazed clay should have absorbed a bit of oil and dust over time, giving it a slightly darkened, mellowed appearance.

- Glaze Contraction: On very old pieces, you might see "crawling," where the glaze has pulled away from the clay in tiny spots during firing.

If the mark looks like it was printed yesterday with a laser printer, or if the "wear" looks like it was applied with sandpaper in a uniform pattern, be skeptical. Modern reproductions often try too hard to look old, resulting in a forced, unnatural appearance.

Spotting Modern Reproductions

How do you identify valuable pottery marks? You look for the quality of the calligraphy. A master potter like Aoki Mokubei or someone from the Nakazato Taroemon lineage spent decades perfecting their craft. Their signature is an extension of their art. If the mark is sloppy, poorly centered, or uses "muddy" colors, it is unlikely to be a masterpiece.

| Master Potter / Lineage | Known For | Mark Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Aoki Mokubei | Literati style (Nanga) | Often uses "Mokubei" in elegant, thin script |

| Kakiemon | Overglaze enamel | Often unmarked, but later pieces use a "Kaki" seal |

| Makuzu Kozan | Meiji Era masterpieces | Very fine, detailed hand-painted marks |

| Nabeshima | Imperial presentation | Often features a "comb" pattern on the foot |

Valuable marks are often accompanied by high-quality potting. The walls of the vessel will be consistent, the glaze will be free of large accidental bubbles (unless it's a specific "wabi-sabi" style), and the weight will feel balanced. A mark is only as good as the object it is attached to.

Conclusion

Decoding Japanese pottery marks is a journey that combines linguistic detective work with physical observation. You start by identifying the type of mark—is it a hand-painted Kanji signature or a stamped seal? You look for helper characters like "Dai Nippon" to establish a timeframe. You check for the "Fuku" mark to see if the piece was intended as a blessing or an export.

Remember that the mark is only 50% of the story. The other 50% is written in the clay of the footrim, the presence of spur marks, and the honest wear that only comes with a century of existence. By comparing the mark's claim against the physical evidence of the piece, you can distinguish between a modern reproduction and a genuine Meiji treasure.

The next time you find yourself at an estate sale or a flea market, don't just look at the beauty of the glaze. Flip the piece over. Look at the "shoes" of the pot. If the characters look complex or the history seems hidden, use a tool like the Relic app to get an instant second opinion. With a bit of practice and the right technology, you’ll be able to spot the difference between a common bowl and a museum-quality masterpiece before you even reach the checkout counter. Happy hunting.

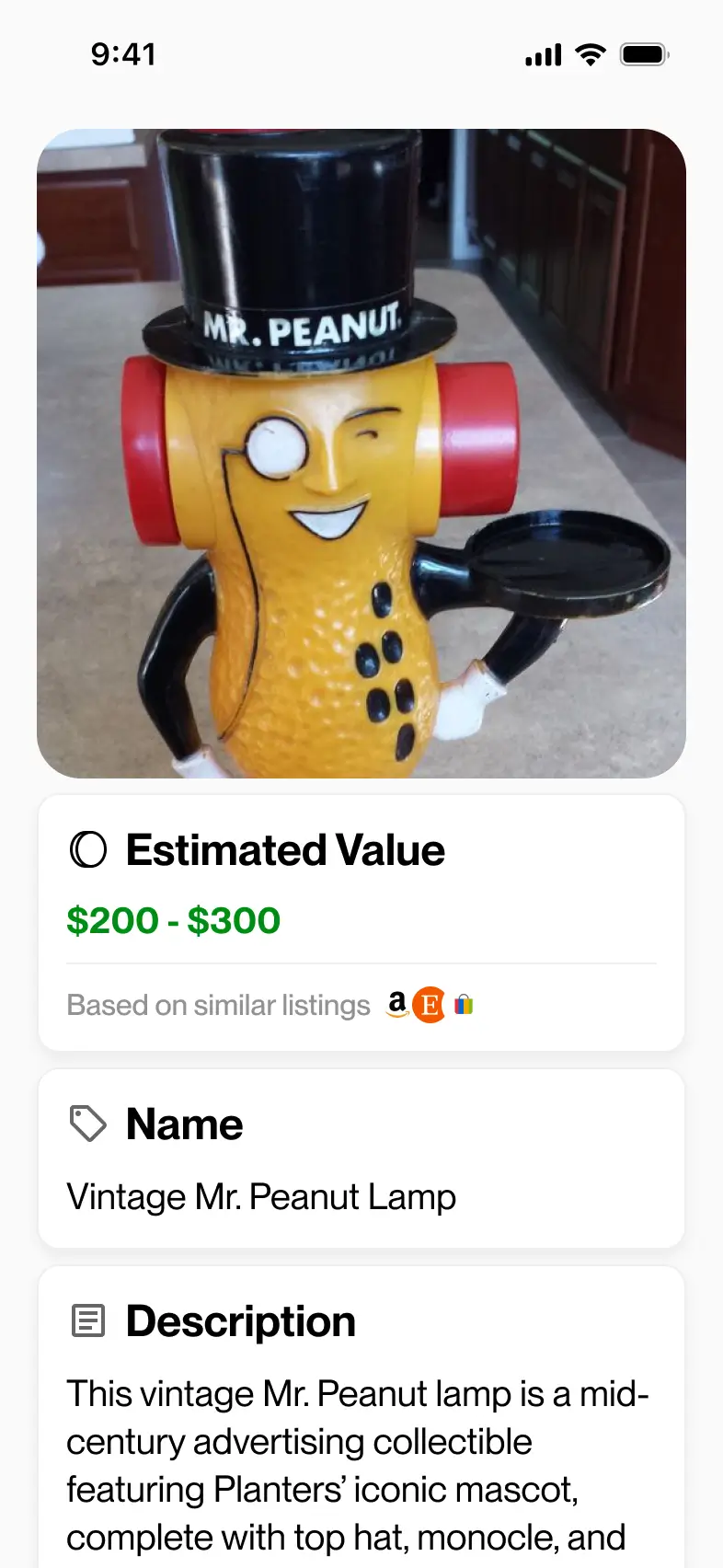

Identify antiques instantly

Point your camera at any antique, collectible, or vintage item. Get valuations, history, and market insights in seconds.

Download for iPhone